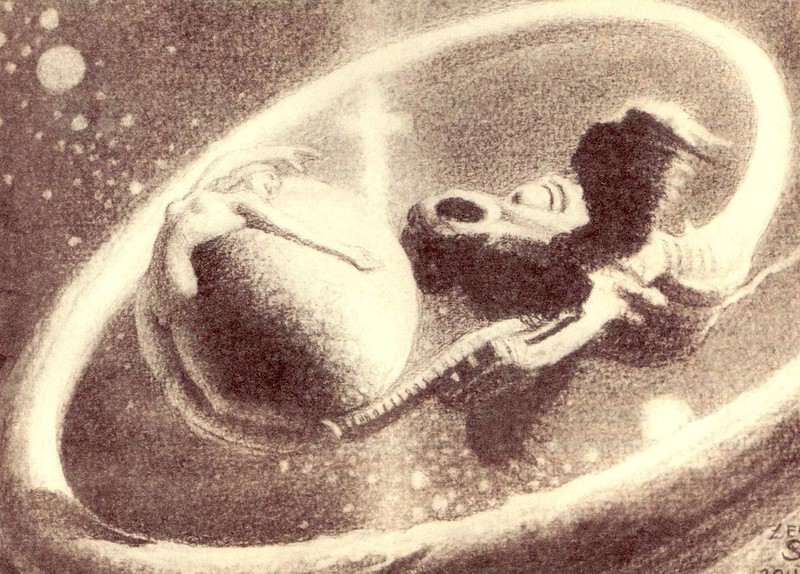

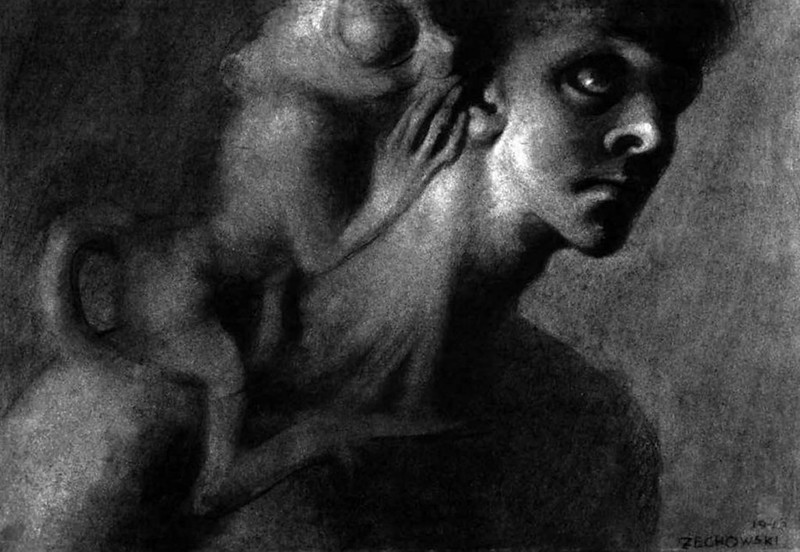

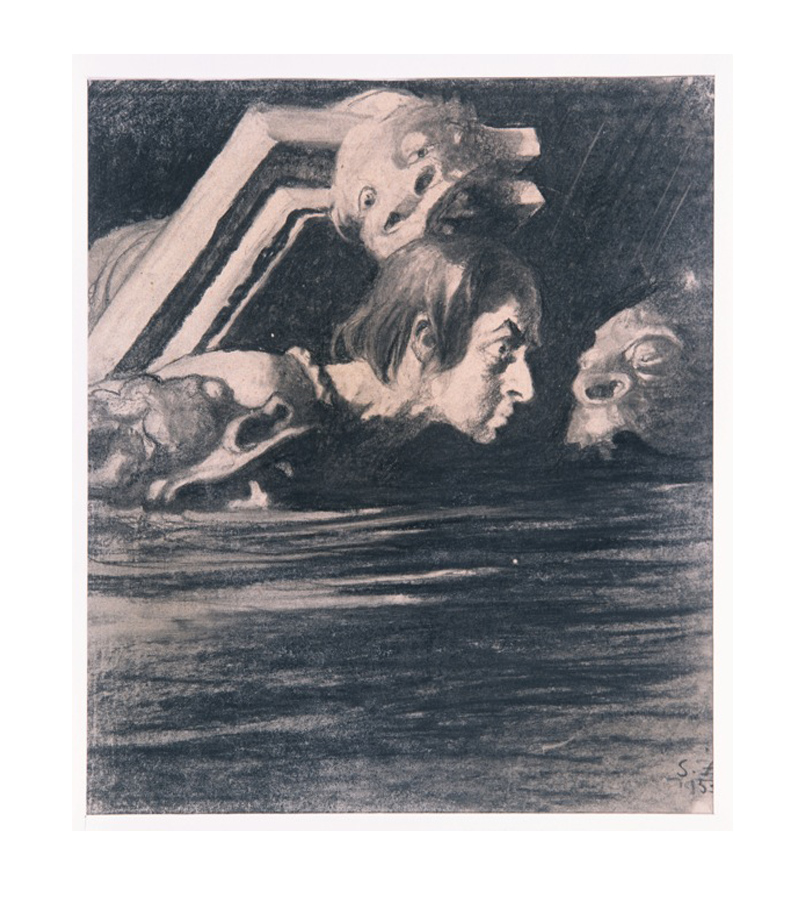

Anhelli And Death, 1947

Anhelli And Death, 1947

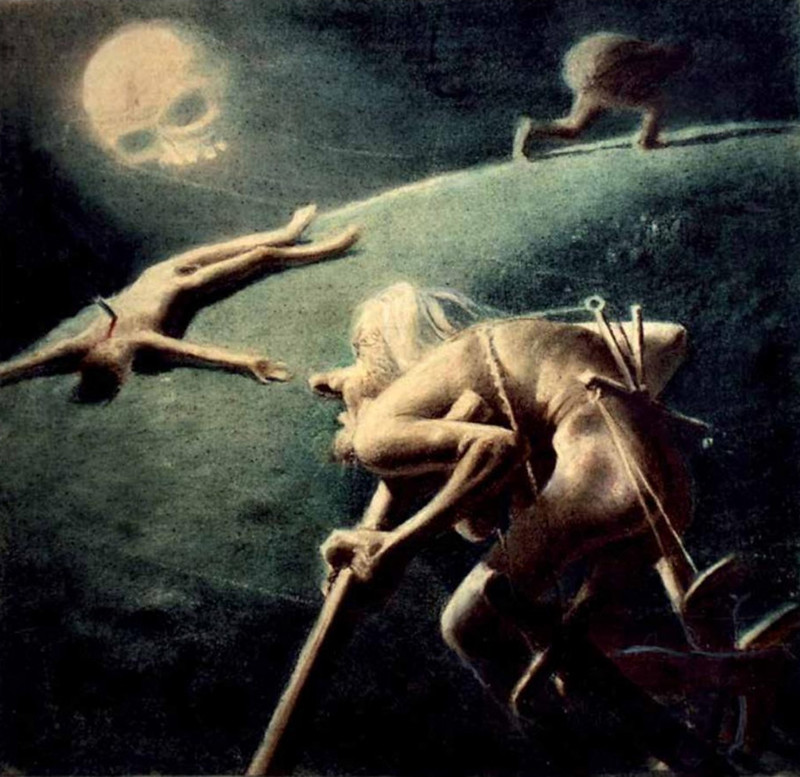

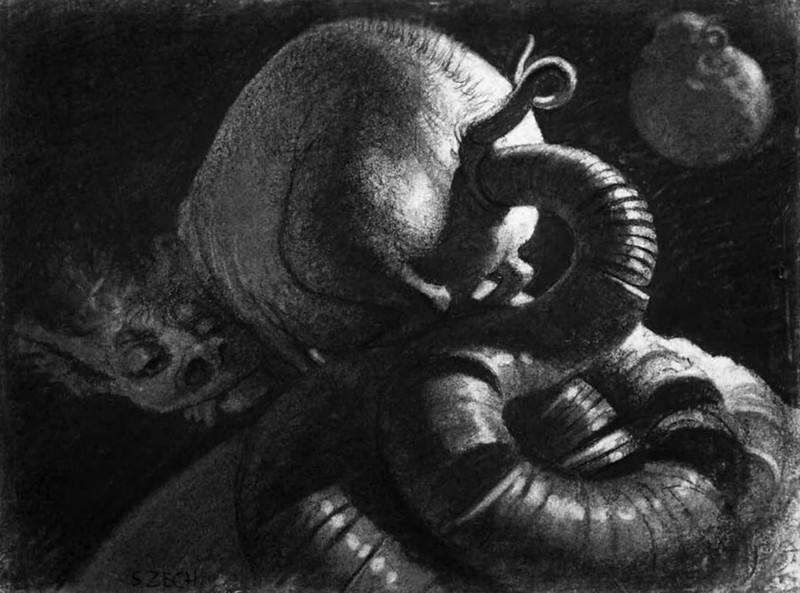

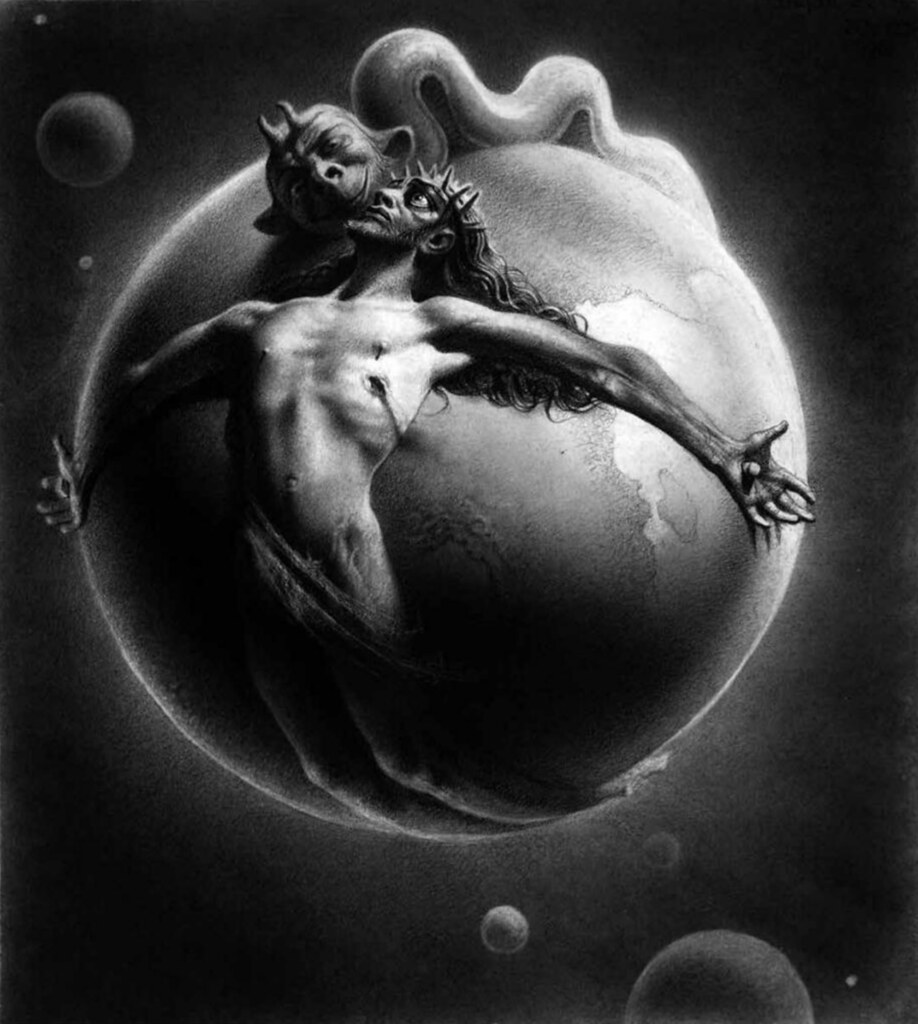

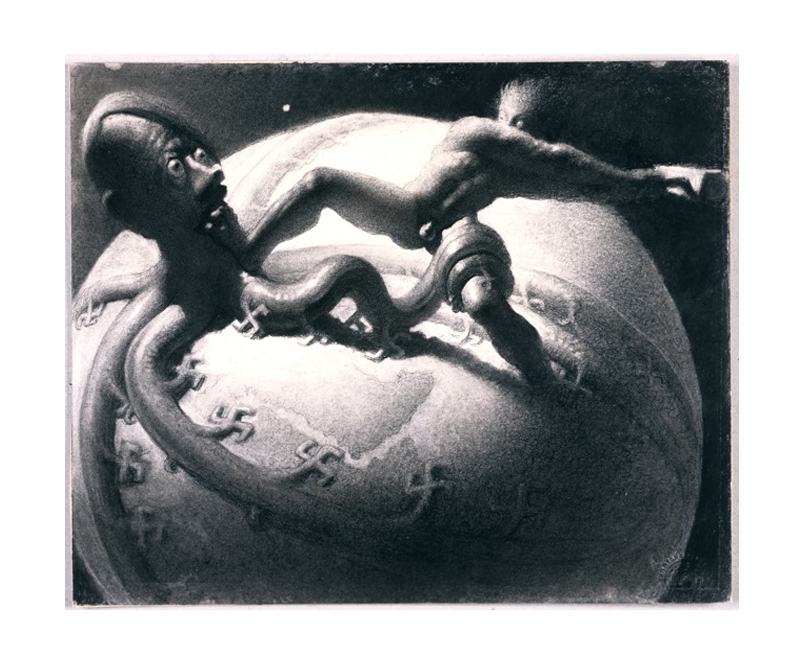

The Death Of The World

The Death Of The World

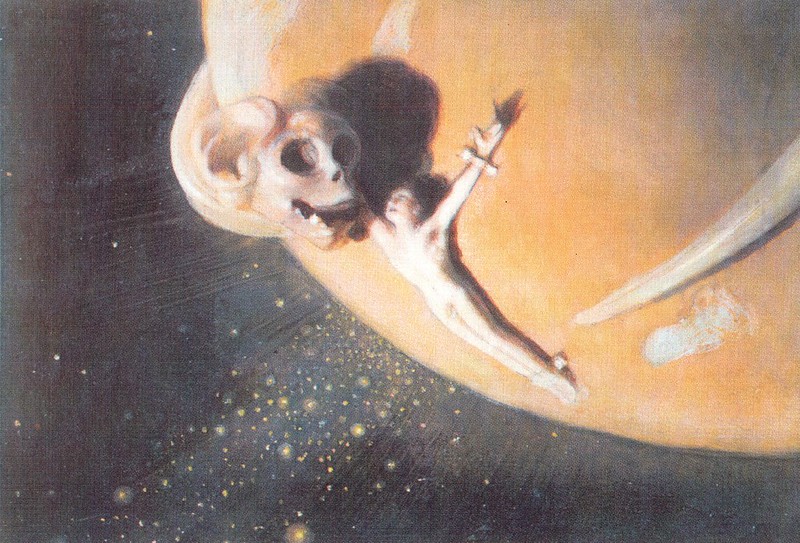

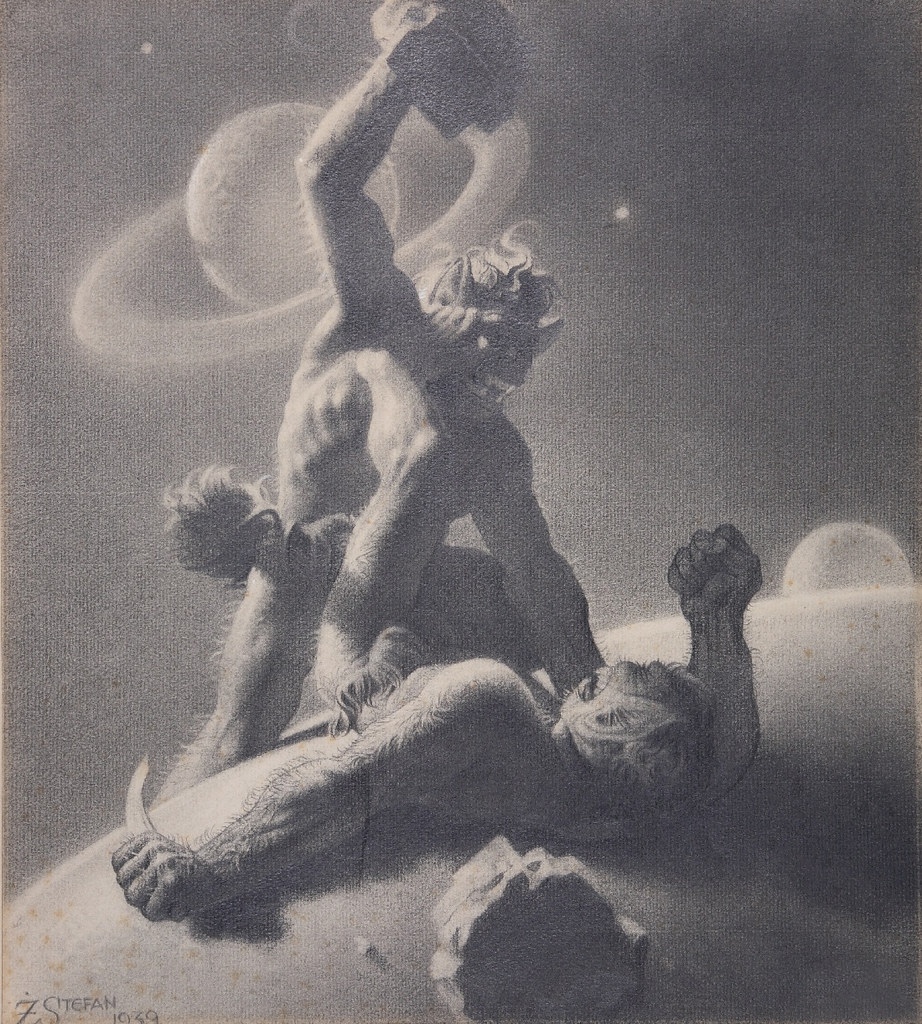

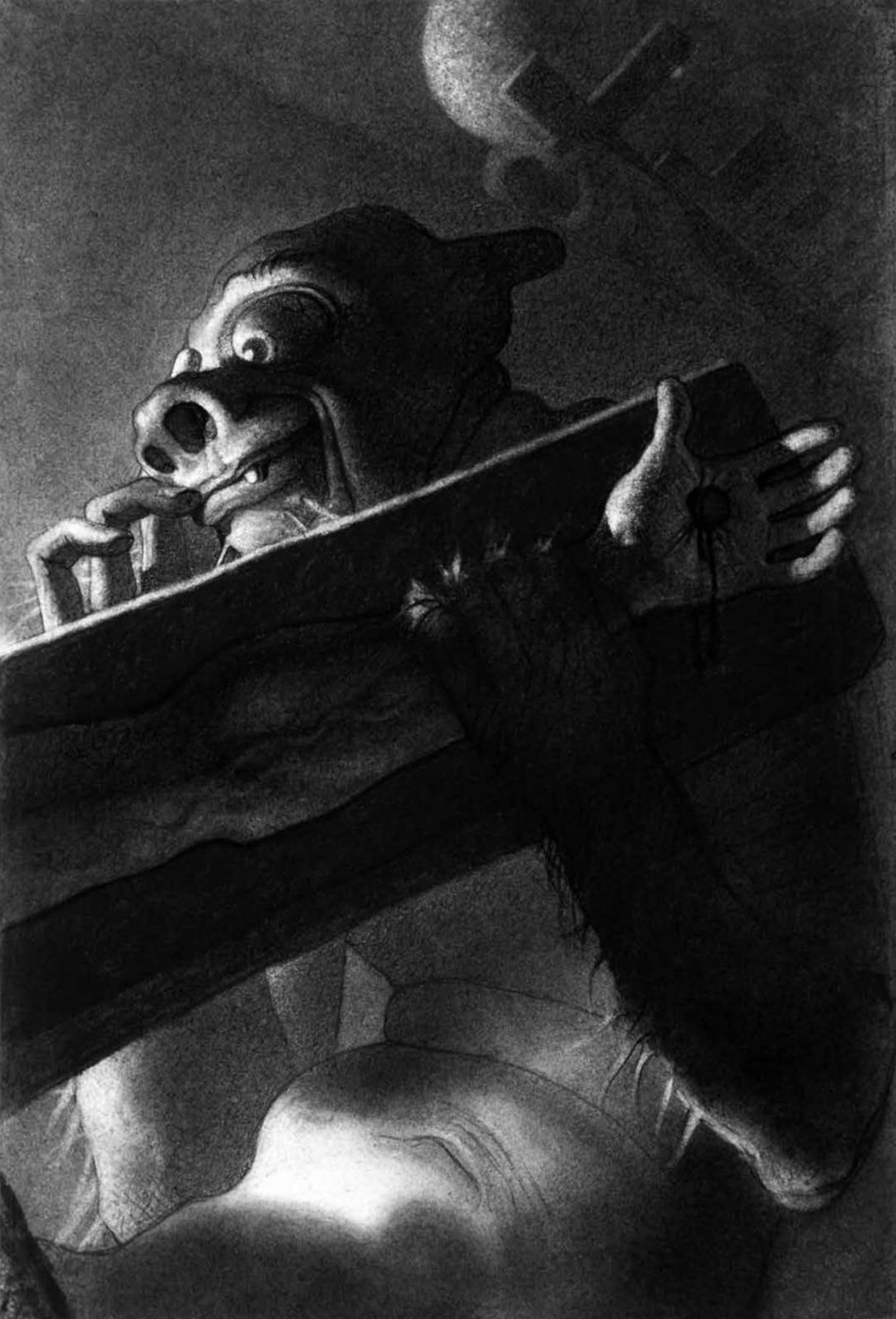

The Original (War Series) 1939

The Original (War Series) 1939 Christ, 1937

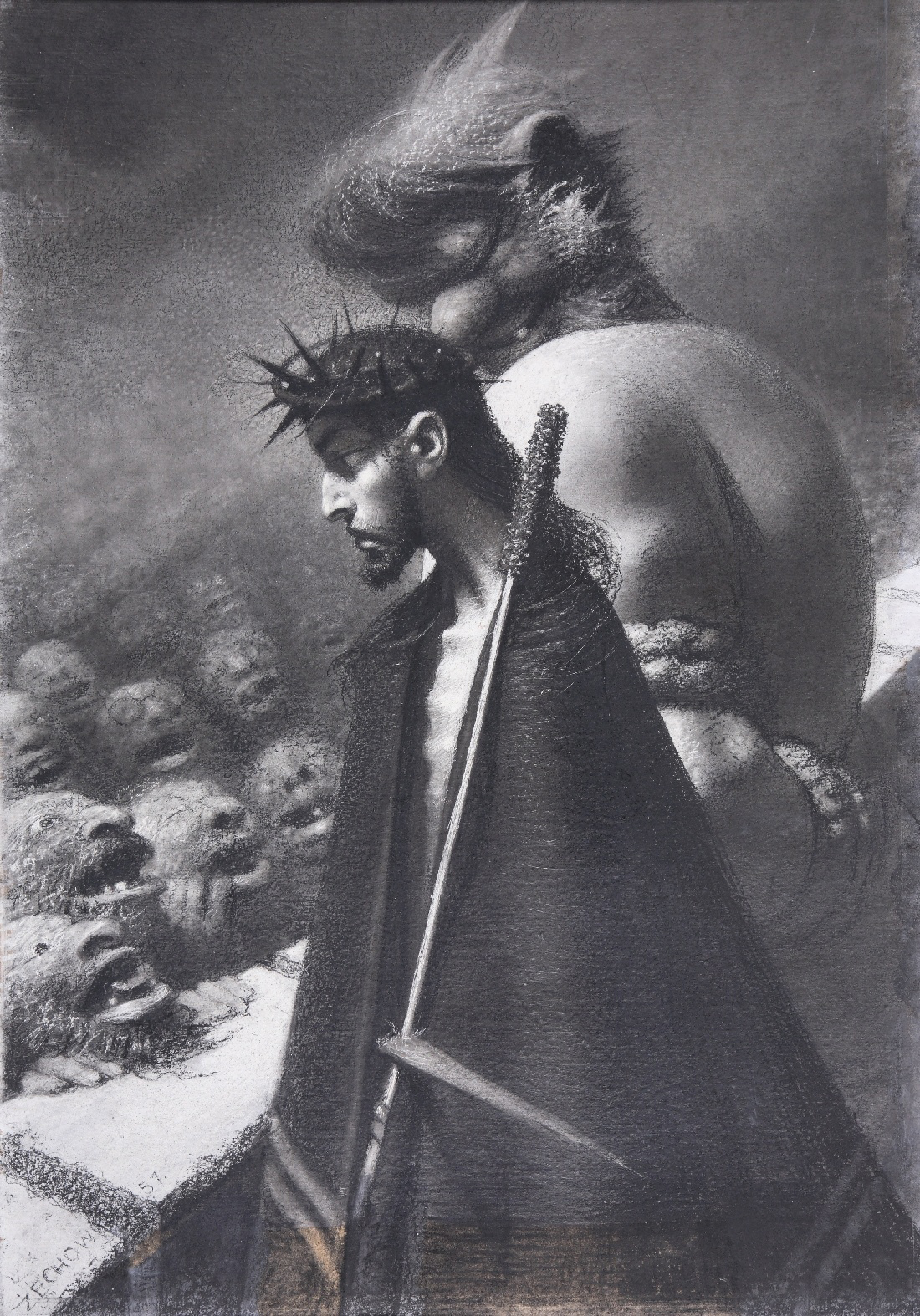

Christ, 1937 Christ in front of the crowd, 1957

Christ in front of the crowd, 1957

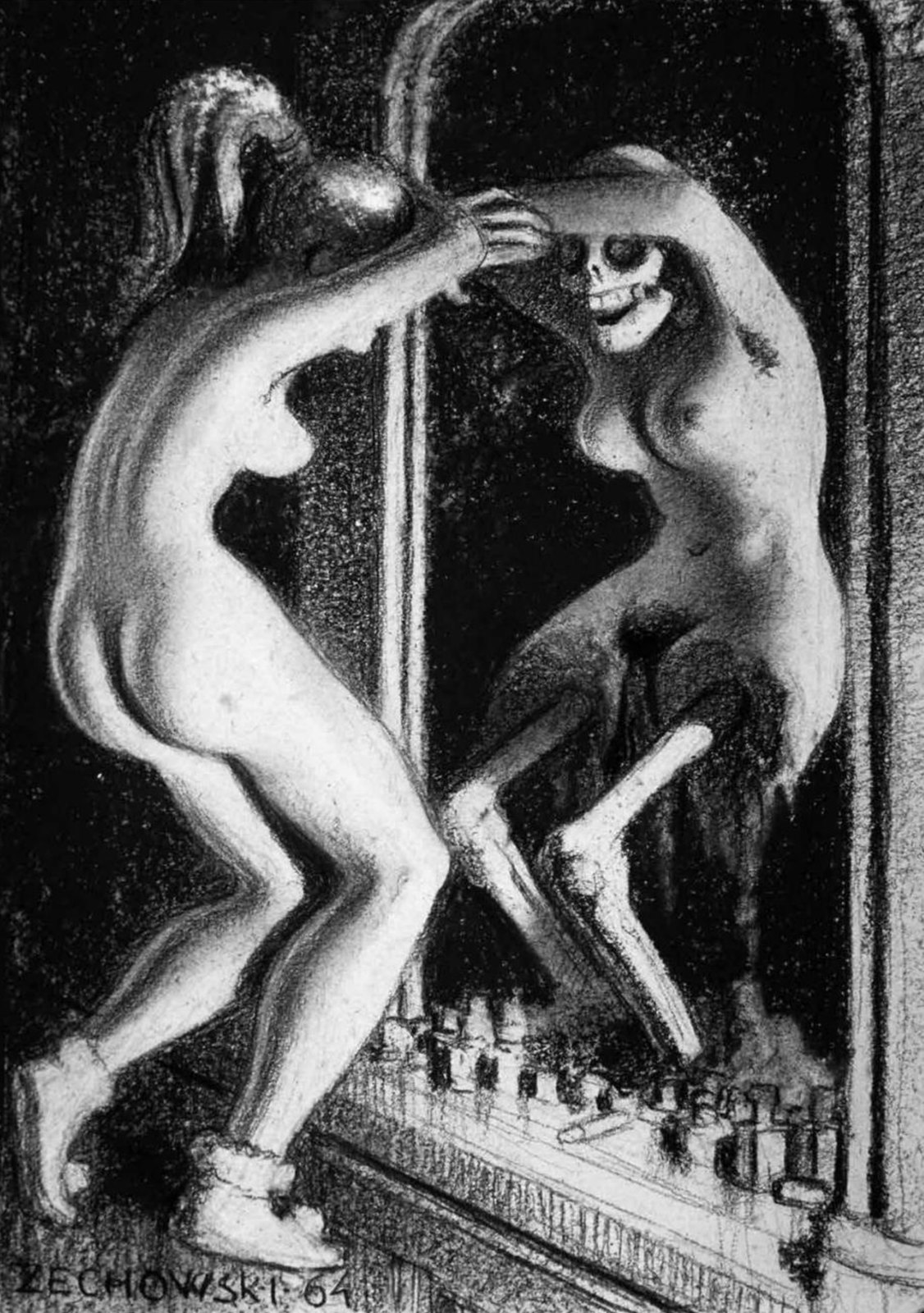

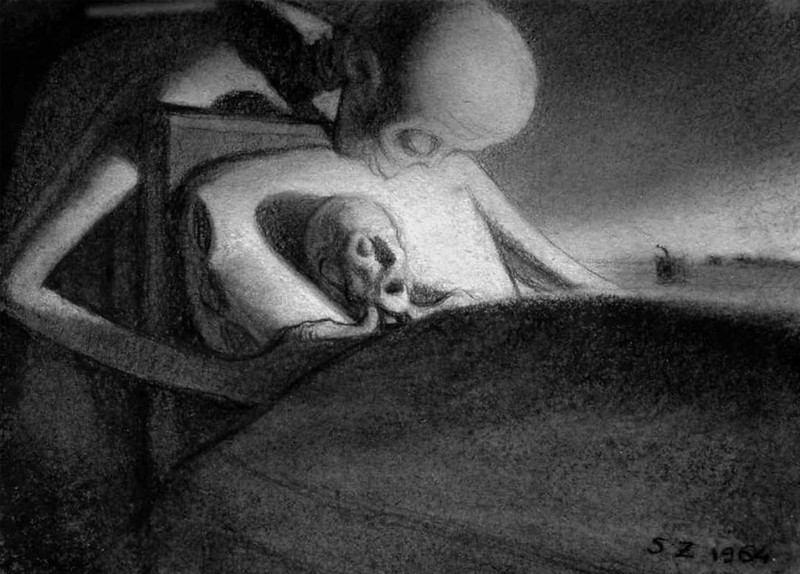

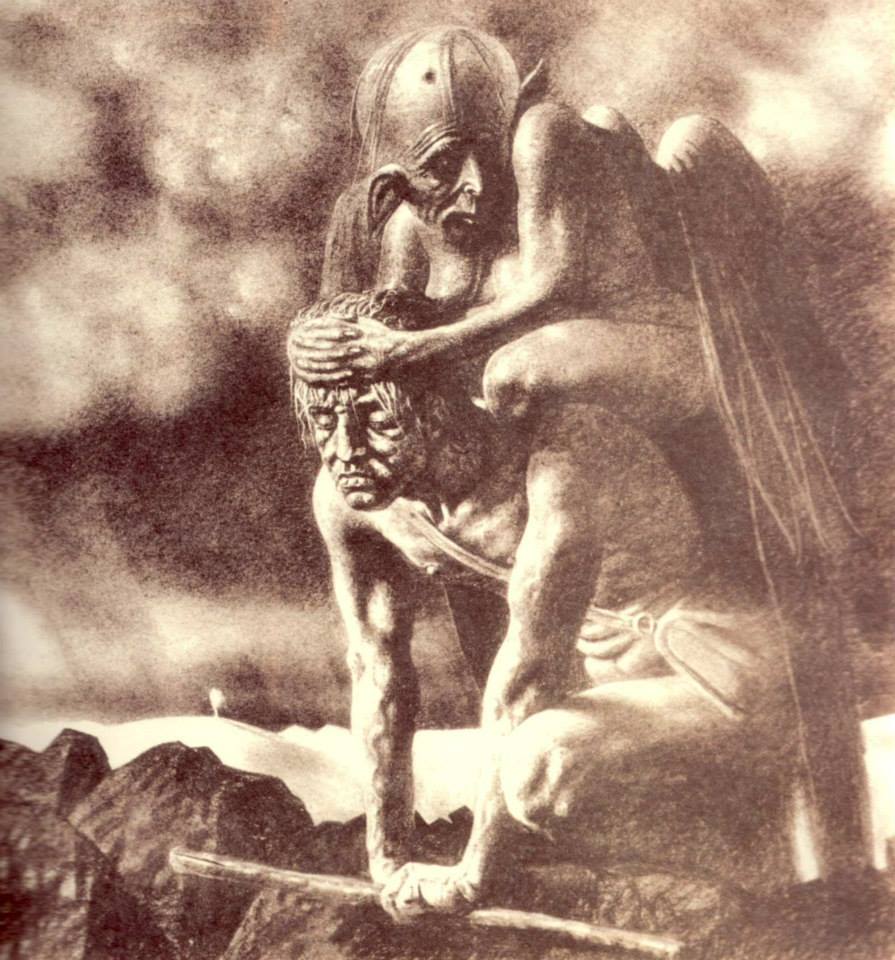

Youth And Old Age, 1964

Youth And Old Age, 1964 Chase, Illustration for "On the Silver Globe" by J. Zulawski, 1956

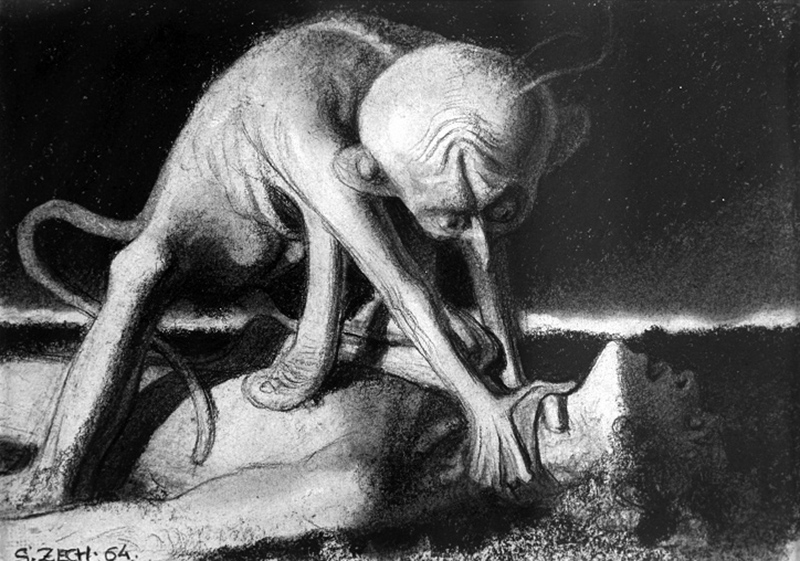

Chase, Illustration for "On the Silver Globe" by J. Zulawski, 1956 Nightmare, 1964

Nightmare, 1964 Unobtrusive Thought, 1943

Unobtrusive Thought, 1943 Between Then And Now

Between Then And Now The Burden Of Life, 1943

The Burden Of Life, 1943 Pilgrim, 1933

Pilgrim, 1933 Smirec, 1964

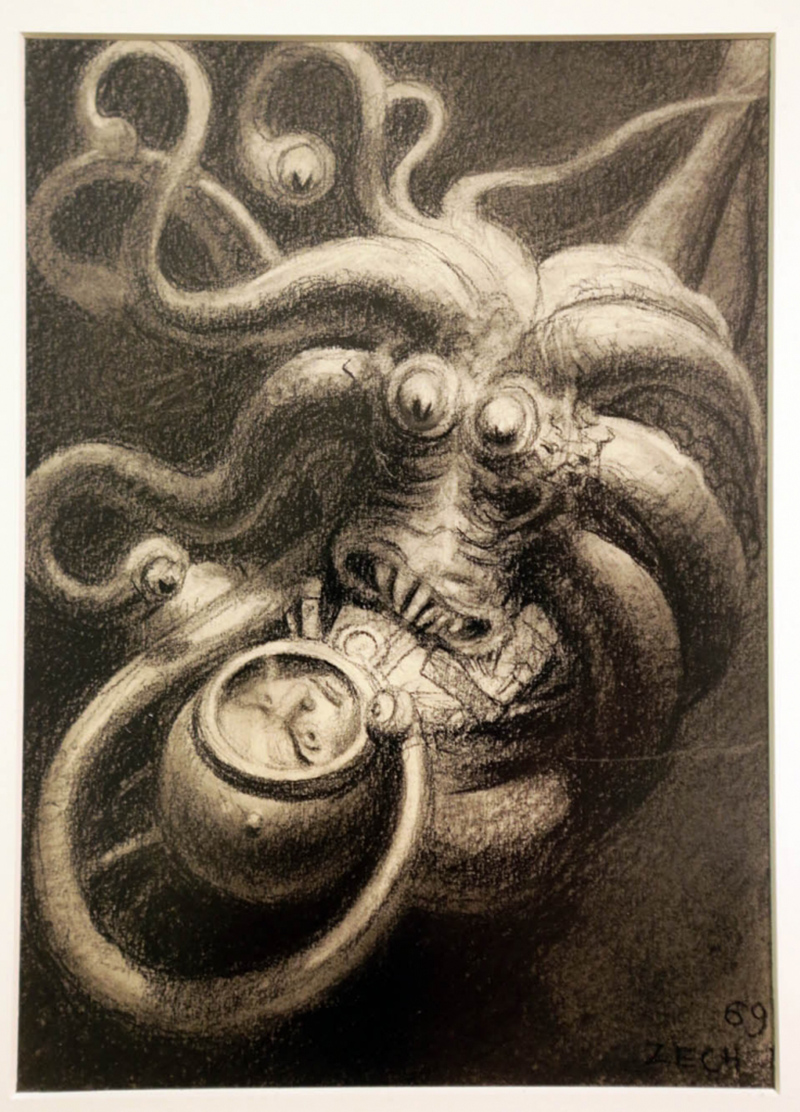

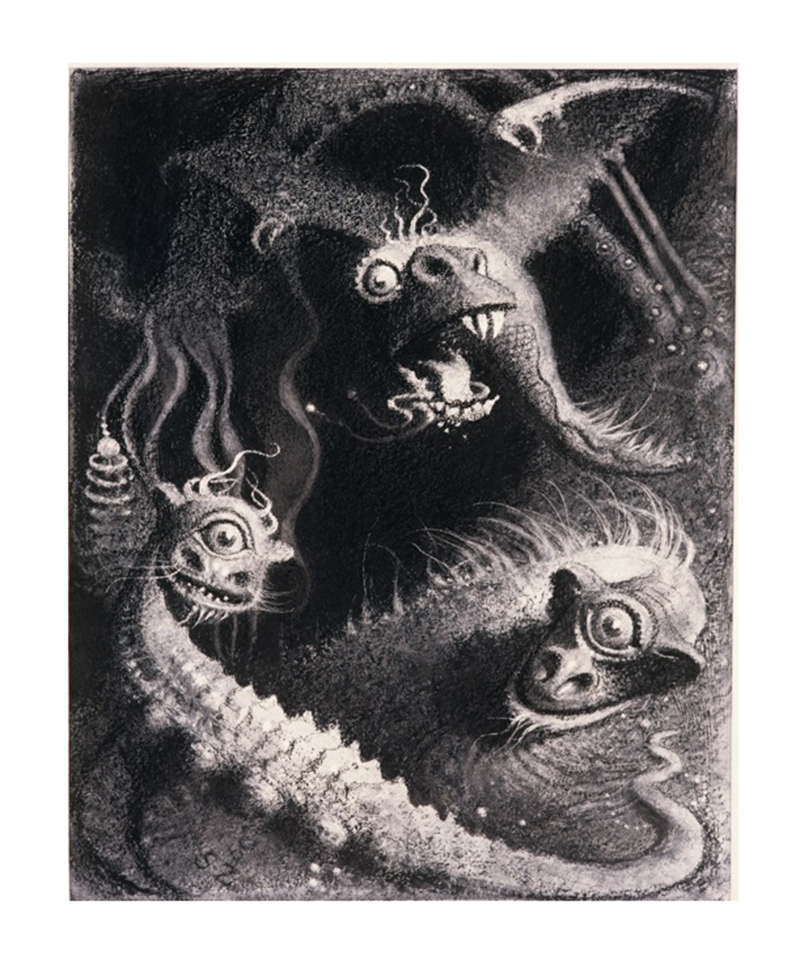

Smirec, 1964 Hydra Mammon, 1943

Hydra Mammon, 1943 Dragonfly, From Childhood Series.

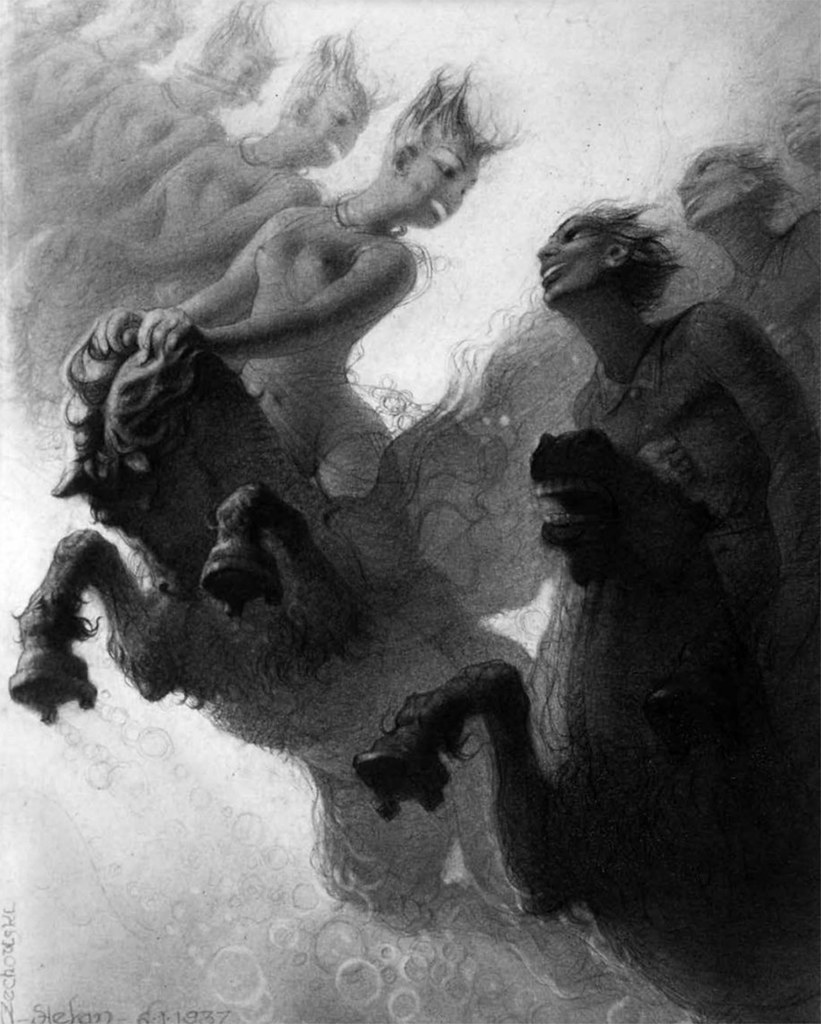

Dragonfly, From Childhood Series. Carousel, 1937

Carousel, 1937 Temptation, 1938

Temptation, 1938 Illustration for Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, 1955

Illustration for Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, 1955 Funeral, 1964

Funeral, 1964 Rama Cross, 1943

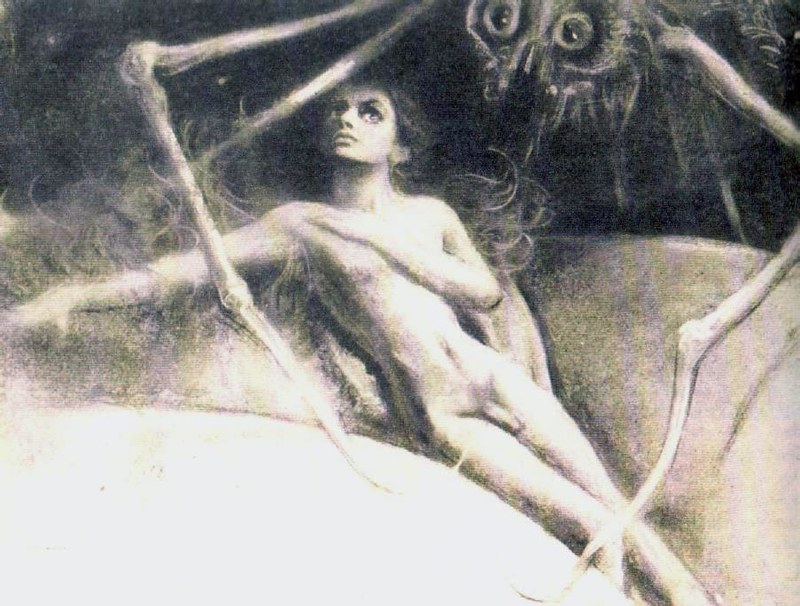

Rama Cross, 1943 Spider

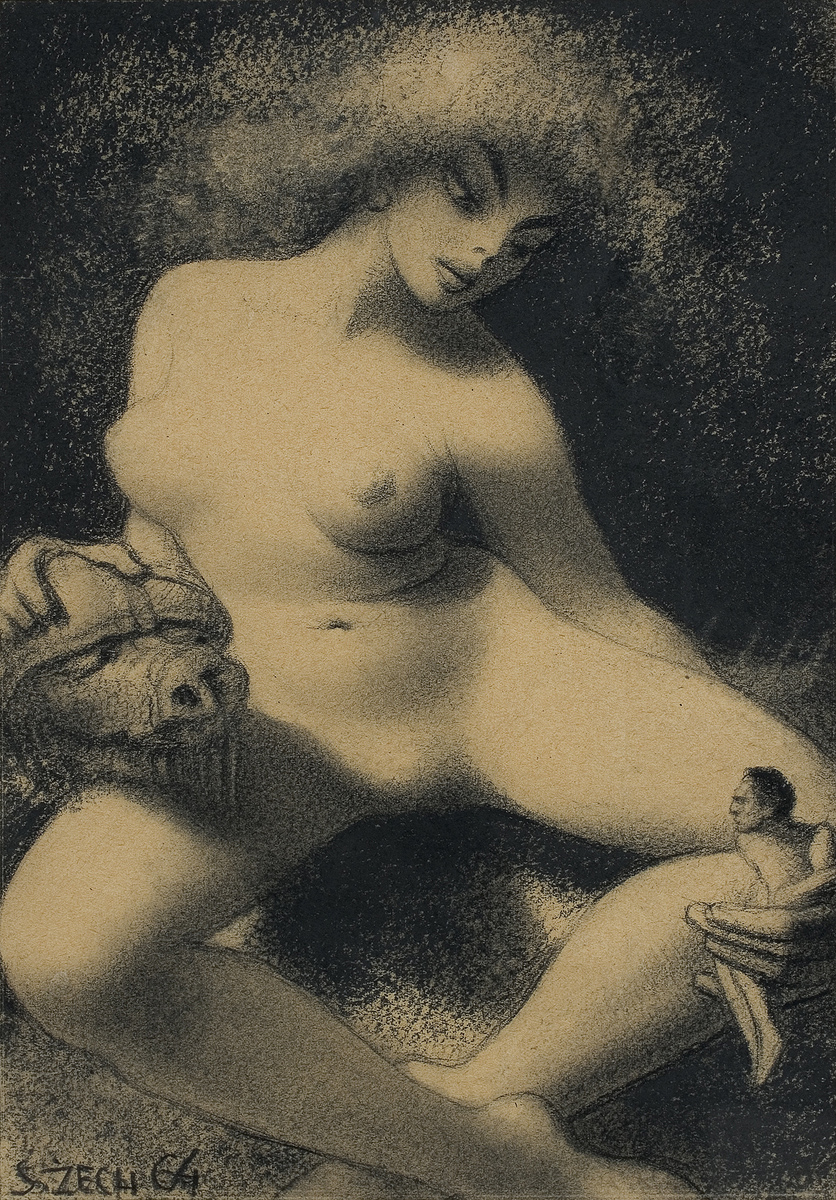

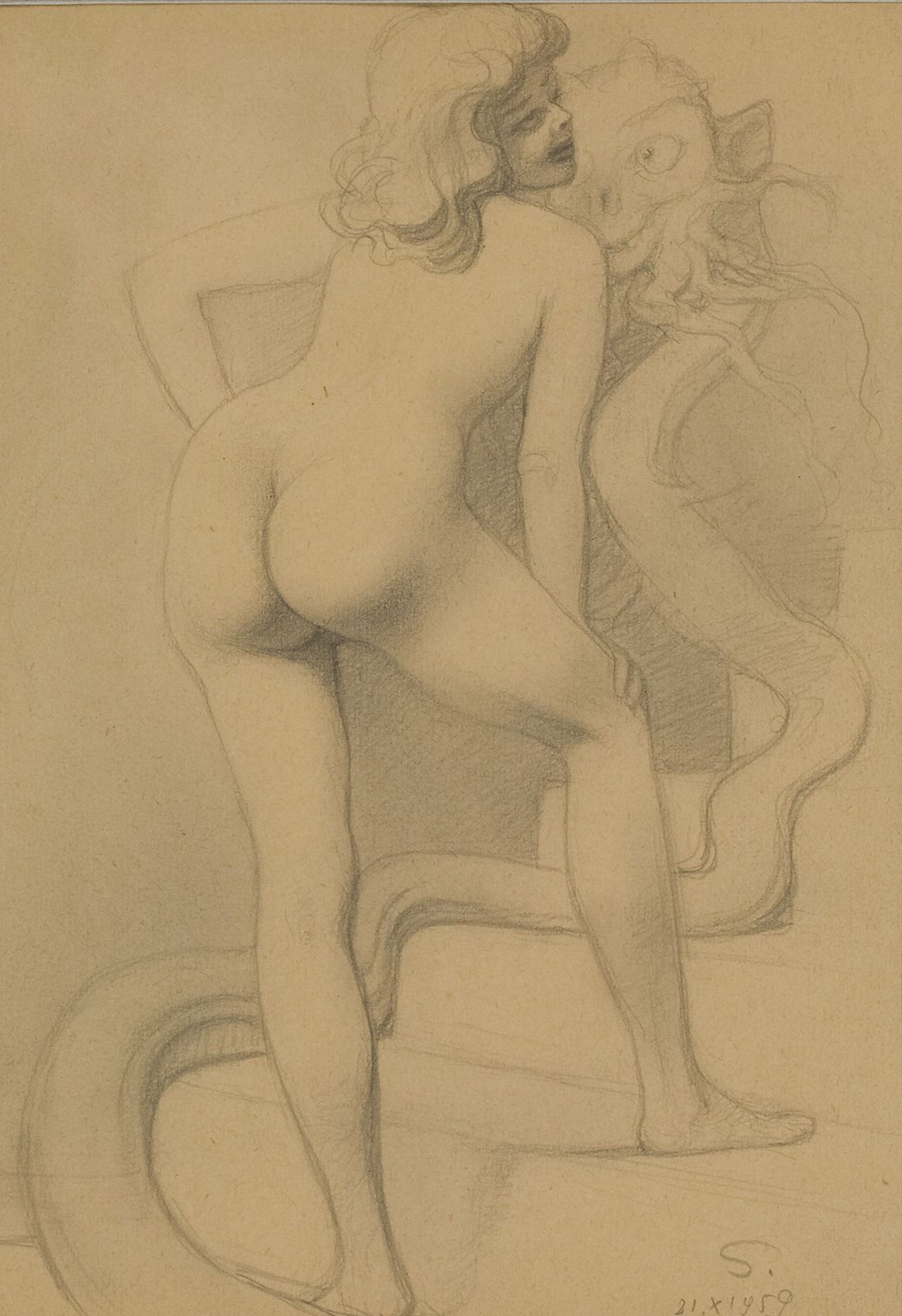

Spider Nude, 1964

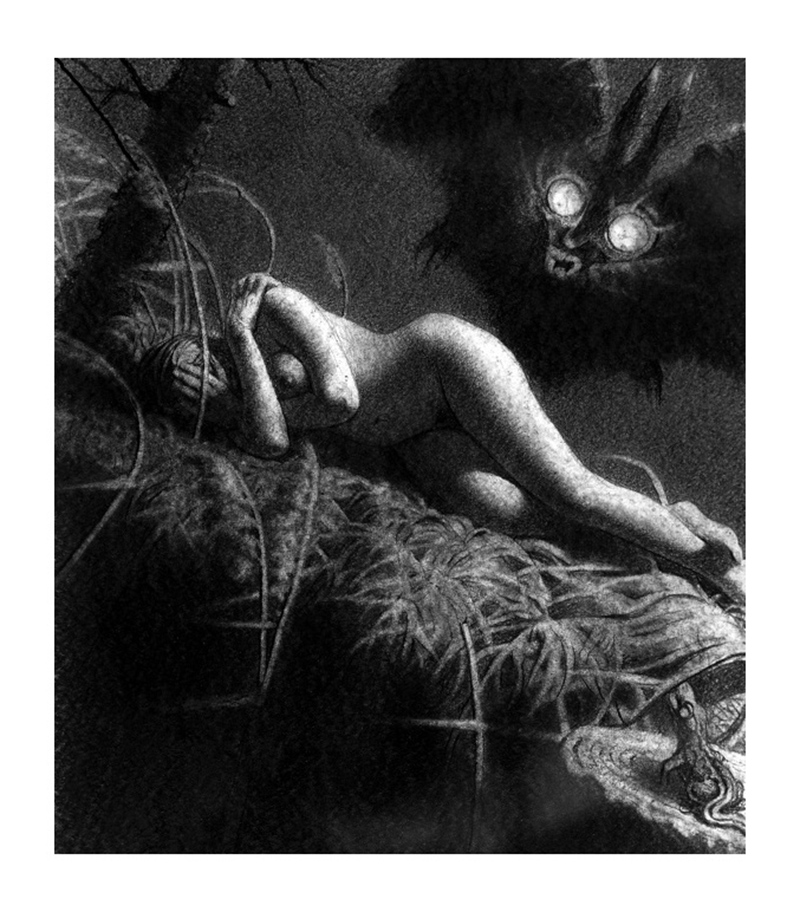

Nude, 1964 Woman and Demon

Woman and Demon Poem about Christ - illustration for Nightmares

Poem about Christ - illustration for Nightmares Burden of Existence, 1934

Burden of Existence, 1934 Orphans In The Channel, 1934

Orphans In The Channel, 1934 Illustration for "On the Silver Globe" by J. Zulawski, 1956

Illustration for "On the Silver Globe" by J. Zulawski, 1956 Dream Mile, 1933

Dream Mile, 1933

"Born on 19th July 1912, exactly one week and decade after another original artist-writer whom he admired, Bruno Schulz, he lived all his life in Newtown Street in Książ Wielki, a village near Kielce. He was the fourth and last son of Wincent and Florentyna, honest and industrious simple folk who in spite of isolated rural poverty ensured education for all their children. One became a teacher and another had artistic talent like Stefan, their lives cut short as victims of Auschwitz thirty years later. For an artist who became so fascinated, indeed mesmerized, by the female form, it may be significant that there were no sisters in the family, nor were more distant relatives mentioned as suitors. A girl at the same school, a one-story thatched 17th century building, remembered that the future artist didn’t join in playground games but stood watching or else read and sketched, traits that never left the outsider all his life.

The first person to recognise his talent was the school headmaster in 1926, who allowed Stefan to draw portraits of those around him during class. Other teachers sometimes even bought the drawings for money or sweets. A developing theme for his work and philosophy from this time was the subject of hate, which he recounted in a diary written all his life. For example, one Sunday when out walking he heard screaming from a victim of mugging who was hit on the head by a stone, an almost biblical memory that he regularly reworked: he asked himself what does it mean, why do people hate each other so much? It was a question that could never be answered, perpetuated in local drunken fights that disgusted him and which featured, allegorically, from his earliest surviving pictures right to the end.

In 1929 the 17 year-old travelled the 60 kms to Kraków, the former capital that became the nation’s cultural heart, for an examination to enter the Ornamental Arts and Crafts School in Mickiewicz Avenue, appropriately named after the national poet he avidly read and portrayed. His still-partly surviving portfolio, with illustrations of another bard’s verse and country scenes that somehow fuse the uncanny with the actual, so impressed the Board of Directors that he was exempted from the theory exam. Indeed, they created quite a stir as a new discovery, which must have lightened the long trek home as he didn’t have enough money for the fare so had to walk the last 30 kms on foot. (The train ticket cost 7 złoty, he recounted 50 years later, the price of food for a week.) The parents’ joy was tempered by worry about how to fund his new life in the city. His diary says he was one of the poorest and youngest students there in his brother’s hand-me-down clothes, suffering hunger and deprivation as well as disappointment with the curriculum (the endless drawing of chairs and pots seemed like an insult) among classmates who included irritating rich girls bored with their new environment. He confessed hunger was the worst part as a developing awareness of the importance of his art transcended the constant humiliation, while school fees were successively reduced due to success. This developing individuality reappeared when he was called-up for the army, a nightmare that also involved solitary confinement on bread and water for drawing a caricature of his officer!

First exhibiting in 1929 with 12 more in the next 8 years, his first solo show in that city in 1930 included pictures of saints, perhaps a reaction to the school experiences. Icons, whether religious or cultural, were a constant motif. After graduation in 1932 he joined a little-known group, the Tribe of the Horned Heart, based on inspiration from the pagan, pre-Christian nation. He was fascinated with the art and ‘haughty personality’ (Ben Hecht) of its leader Stanisław Szukalski (1893-1987), whom he deemed a master though later questioned his personality and fell-out (much of his work was destroyed by the Nazis, including his own museum). They were on parallel paths, the elder painter having one of the most singular theories for art and mankind that there has ever been; his ashes were spread, significantly, on Easter Island. Outliving the disciple, his reputation revived around the same time in the 1980s and has been sponsored by Leonardo diCaprio. After leaving this group, who were somewhat against the tide when experimental movements such as the Artes (formed in Lwów then moved to Paris) held sway, Żechowski returned to book illustration which resulted in its own controversy. In 1936, on the recommendation of the artist Marian Ruzamski (1889-1945), he visited the writer Emil Zegadłowicz (1881-1941), a magnet for controversial cultural figures. In his rambling country mansion, among sculptures and wall-paintings of demons mouthing aphorisms outside an altar-room once used by a Christian sect, he shared a ghostly experience and ran shouting outside. While there he contracted ’flu and the family nursed him while becoming close friends, a rare experience for the loner described by another visitor, the Socialist Leon Kruczkowski whose book he later illustrated with Flemish-like detail, as ‘quiet, confident and hard-headed but not witty’.

Zegadłowicz was an individualist in a kindred vein, later completely ignored by C.Miłosz’s arrogantly-titled The History of Polish Literature in spite of writing an early study of Wilde and modern art movements, dramas and poetry including Chinese forms like Ezra Pound. His novels combine a daring exploration of inner drives and passions with awareness of Nature and folk customs of rural communities such as the Tatra highlanders. He told the artist that his drawings conjured in front of his eyes the doyen of Decadence who had died a decade earlier, Stanisław Przybyszewski (see Wormwood #6), an intriguing collocation as the three explored similar aesthetics. His guest confessed, shamefacedly, that he had read almost nothing by that writer who was once famous across all Europe, but in childhood wanted to read his 1890s novel Homo Sapiens until his brother took it first saying it was not for the young. Zegadłowicz was an important conduit for such material during the inter-war years, when for example he met Bruno Schulz and given a couple of drawings, which as we saw on our visit to the home are still lovingly kept by the writer’s daughter. She still remembers Stefan’s thick dark hair when he used to shave out in the garden during his stay.

The artist gave them 30 drawings as a gift and contributed 37 illustrations to the writer’s new novel, Motory (1937, The Motors). Due to those difficult times, when the establishment controlled the media, the novel was issued by a fictitious publisher that was the author himself, but soon almost all the 1,000 copies were confiscated and the illustrator accused of ‘anti-government rebelliousness and immorality’. The artist’s wish to be associated with this work is in itself significant—at first he was disappointed by the erotic scenes that were too naturalistic for his romantic spirit and view of love, but decided to choose only the fragments he personally liked. Żechowski usually preferred the classics of Polish and European literature from earlier periods, such as Dostoevsky, Edgar Allan Poe, Nietzsche, and the Romantic icons Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki (whose poem “Anhelli” he illustrated at school). Their evocative, almost mythic portraits reappear as a touchstone during the alienation of everyday life. Apart from a few short stories he read all Dostoevsky’s work, which he described as like going to a dark witch-world where the poor, innocent, ill and angry people dwell, a space very much occupied by himself too in the cramped village cottage at the end of a lane and round the corner from the surprisingly massive church. He spent a couple of months away from school with his work, buried in thinking about the sense and meaning of the world around him, but when he also read Poe (which was possibly illustrated by Odilon Redon) he felt himself losing the will to fight to change his situation. Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, translated by the Decadent writer Wacław Berent, sent the painter into raptures from its very first words.

The visual artists that Stefan Żechowski admired are also significant for an understanding of his own art—not for explication, because they primarily registered on his consciousness rather than the images and style, as with all true originals (in this respect it’s the same with the evocative art of the Quay Brothers, who first introduced us to the Polish master’s work in their studio). Apart from the already-mentioned Szukalski, whose strange creativity mysteriously ‘confronted’ the prodigy before emigration to America, contemporary artists are noticeable by their absence from his stated influences. At college he would be the first and last to leave the National Museum on Sundays gazing at the famous canvases of Szukalski, Artur Grottger, who died aged 30 and had a famous love affair with a female patriot, and Jacek Malczewski as well as his ‘teachers of light’: Leonardo da Vinci, Correggio, Rembrandt and Reubens whose work of ‘divine features’ also featured in Michelangelo’s sculptures. One exception to this pantheon was an interest in the more recent ethereal Symbolism of Arnold Böcklin. Before and during the war he created various cycles entitled “Childhood Memories”, “Dreams of Power”, “War”, “Summits”, “Hymns to Nature”, and “Ill Earth”, as well as essays on free-will, Christ and Satan, subjects that allow a glimpse into his thinking during the mindless engulfing of Europe.

Poland was soon placed in Stalin’s grip, there was no middle ground and little choice but to accept the regime’s Social-Realism or else be ostracised and starved if not imprisoned. From 1946-1949 Żechowski designed a series of thirty postage stamps on Polish culture along with sculpture-like portraits of Lenin and Marx (as well as Chopin, Paganini, Nietzsche, Dostoevsky, and Plato), the following year receiving first prize at a national exhibition as well as the Gold Cross of Merit in 1955. At this time he illustrated a new edition of Emil Zegadłowicz’s most famous novel, Zmory (Nightmares) which was made into a film by Poland’s foremost director Andrzej Wajda, as well as the well-known Jerzy Żulawski’s On the Silver Globe. After the short-lived thaw following Stalin’s death in 1956, he withdrew from public life.

Three years earlier, while away, he heard that his home in Książ had been set on fire by a neighbour. He lost his diary, which involved 23 years of his life, drawings including some of the “Anhelli” series, and correspondence with writers and artists. The motive for the arson is unknown for sure, but when we visited the Muse of his art, his widow Marianna Żechowska, we could see that the home is still closely-bordered by other cottages. Almost unchanged from her husband’s portrayal, and the time when the younger girl used to supply him with books when working in a bookshop, she kindly showed us unpublished drawings from his prodigious albums along with decorated artefacts that are little known. The astonishment that the art provokes cannot be adequately conveyed in a narrative, but it is comparable to the shock that this wondrous treasure-trove of a lonely artist, whose ideal was to convey a unique vision, should be so little known in the world." - quotation taken from the in depth biography of Stefan's life by Brian R.Banks & Marta Mazur.

Image sources include Stefanzechowski.com, National Museum in Kielce and DESA Auction House

A documentary on the artist titled "The Hermit" by Ryszard Wojcik was originally shown in Poland. While not subtitled in English, it is available to watch in its entirety here.

1 comment:

What a great artist. Thanks for this post.

Post a Comment