"In February 1830, Scott was recovering from a first paralytic stroke. J.G. Lockhart, hoping to distract his father-in-law from working on more arduous enterprises (preparing the Magnum Opus and writing Count Robert of Paris), suggested that he write a small volume on witchcraft for 'Murray's Family Library'. As Scott had a comprehensive collection of books on the subject immediately to hand at Abbotsford, Lockhart hoped that it would be a relatively easy project to complete. Instead Scott, who enthusiastically greeted the idea, merely added it to his task list. It was a theme that had fascinated Scott since childhood. He had previously proposed collaborating with Robert Surtees on a study of demonology in 1809, and with Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe on a comic selection of supernatural tales in 1812. In 1823, he had even written part of a dialogue on popular superstitions which had failed to attract a sufficiently enticing bid from Constable.

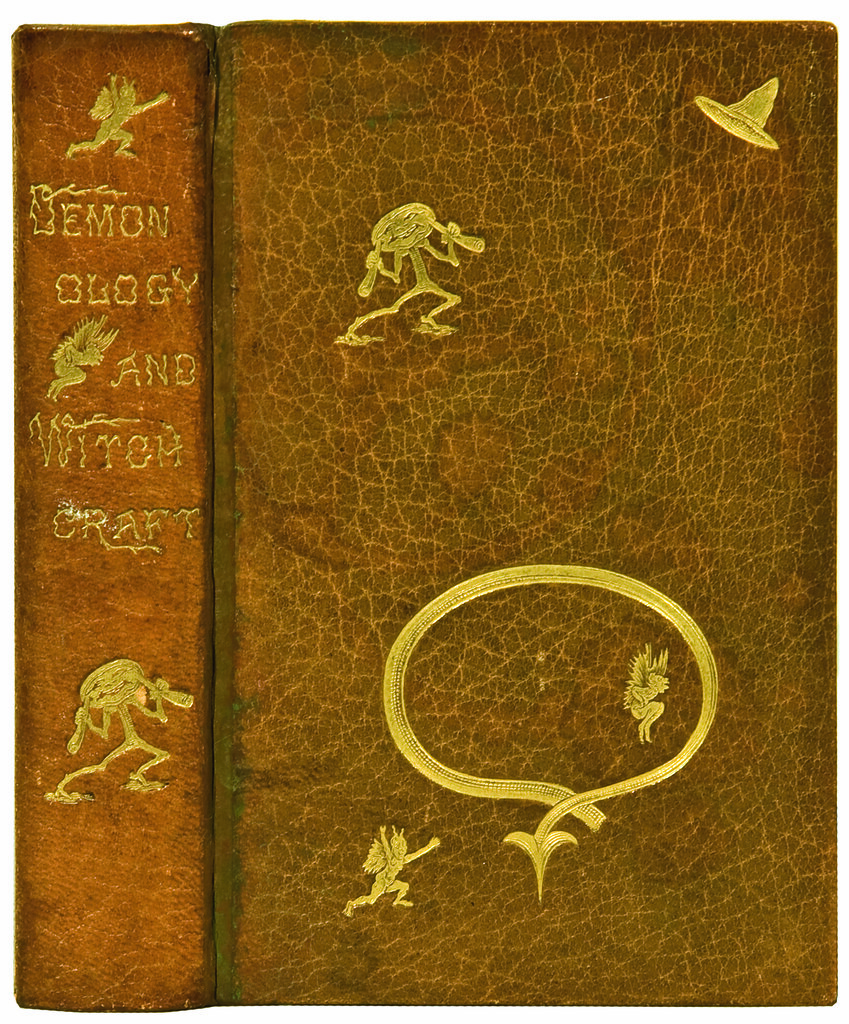

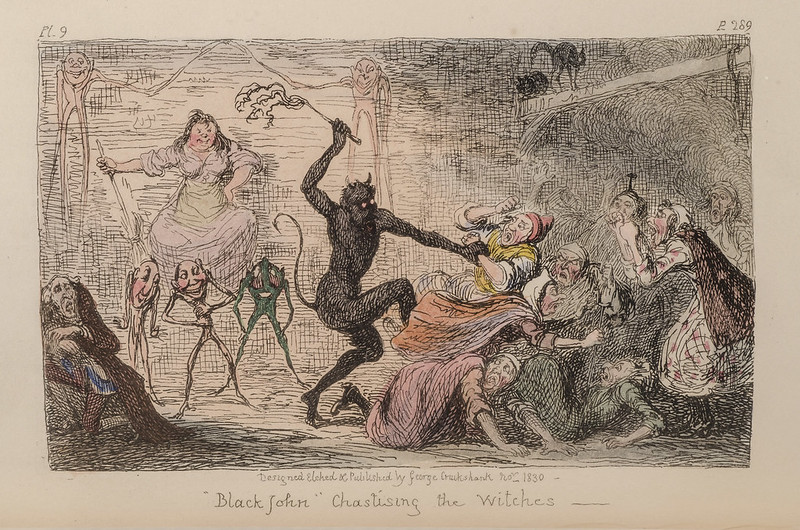

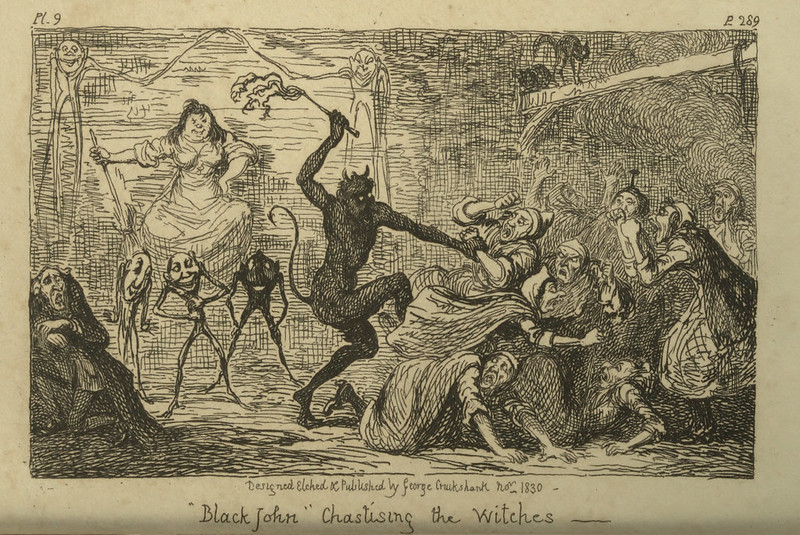

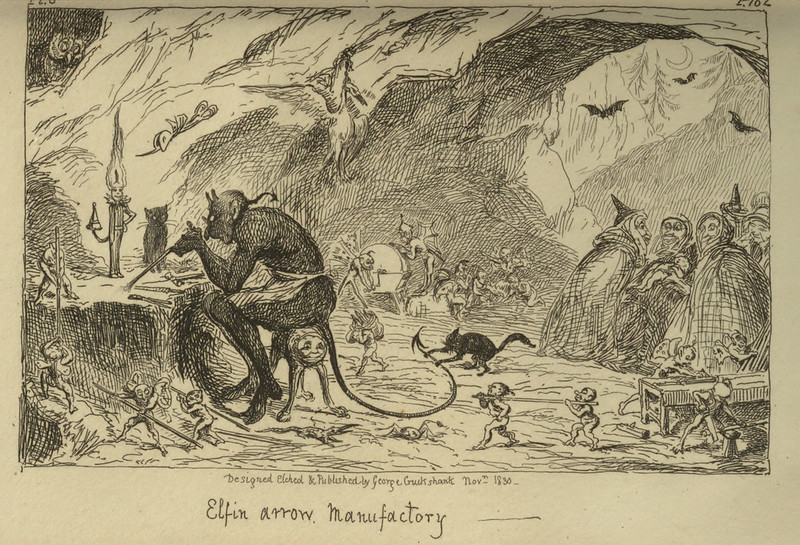

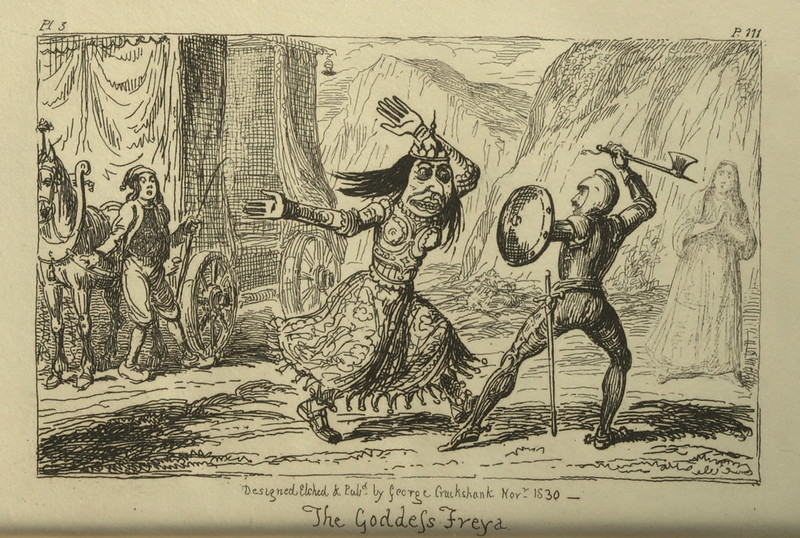

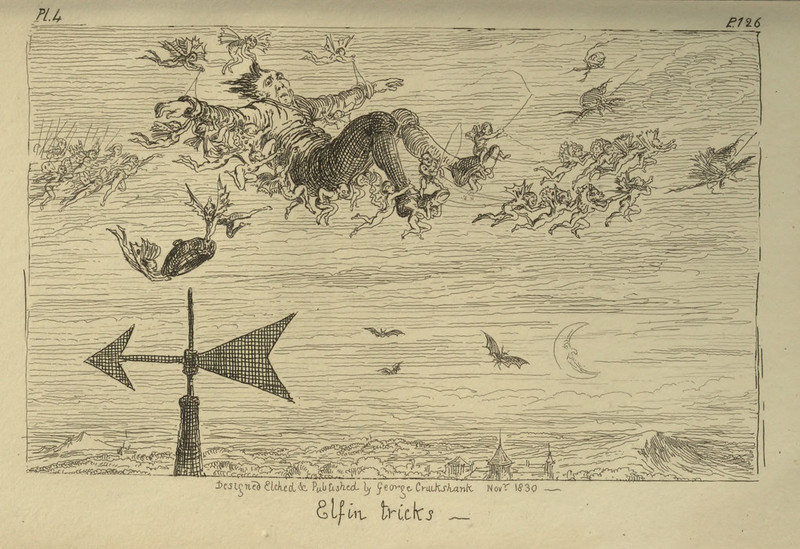

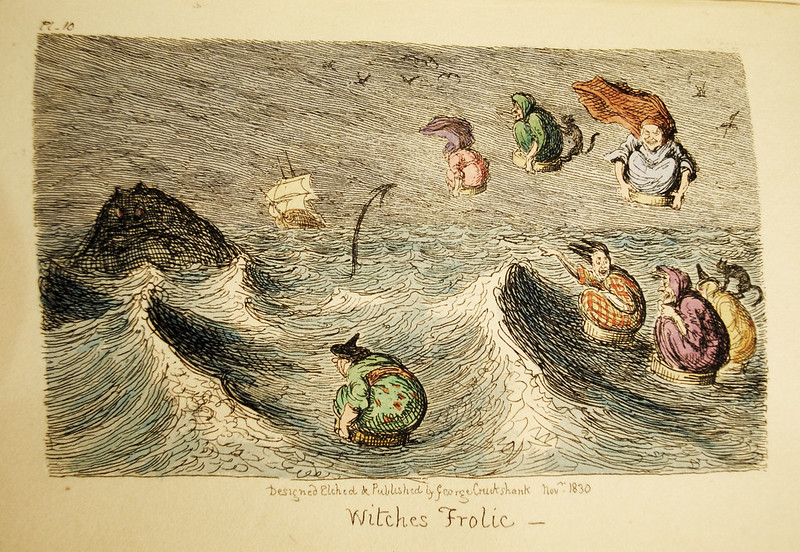

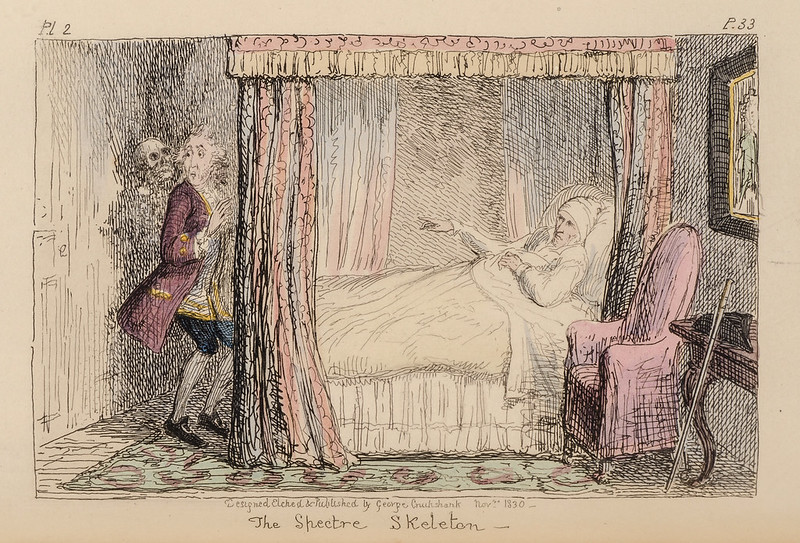

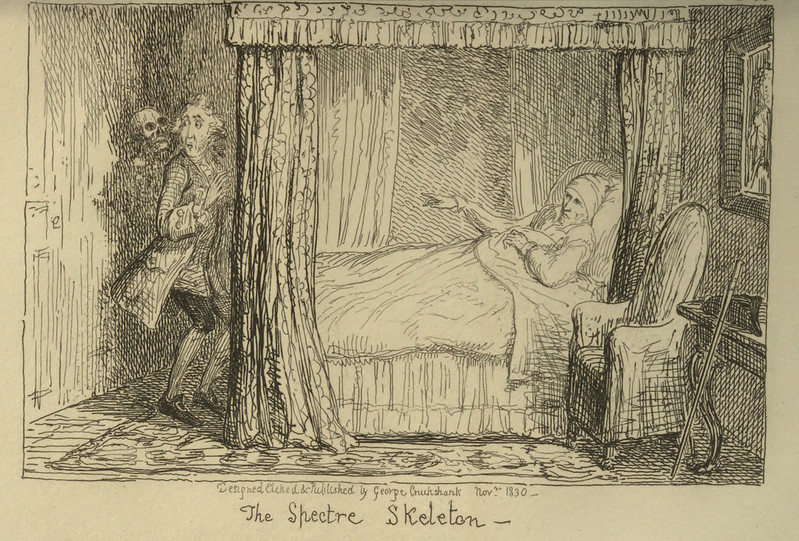

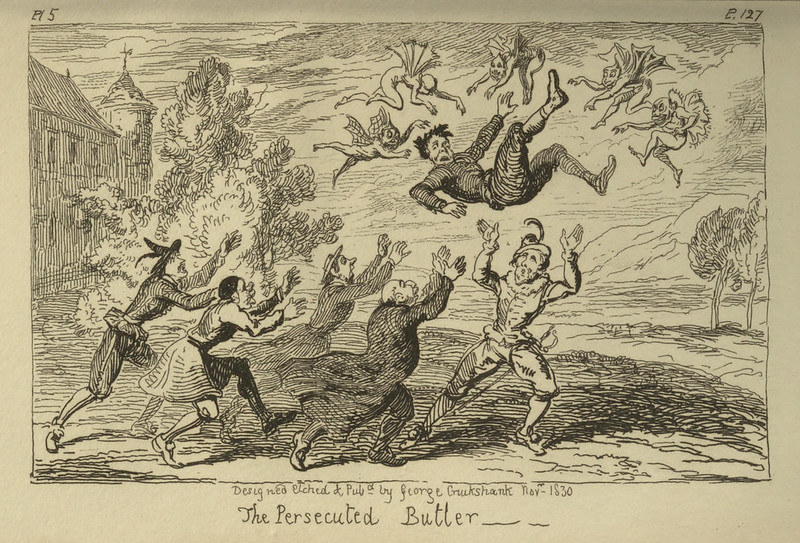

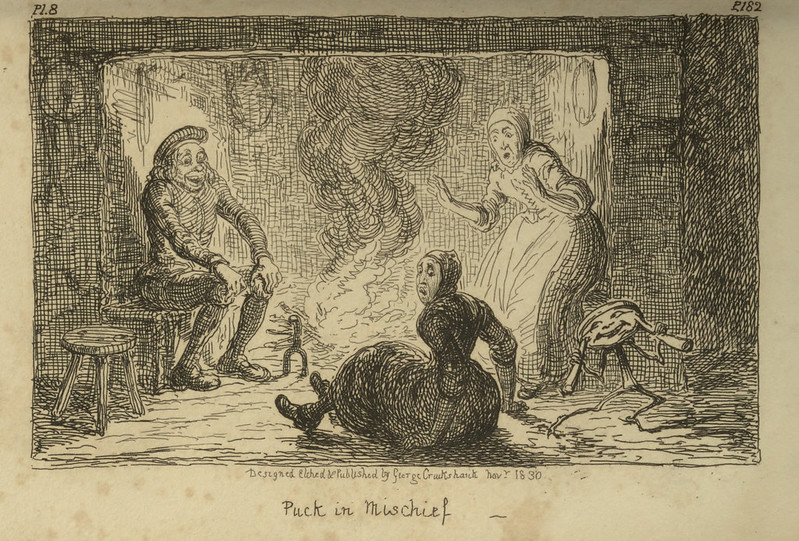

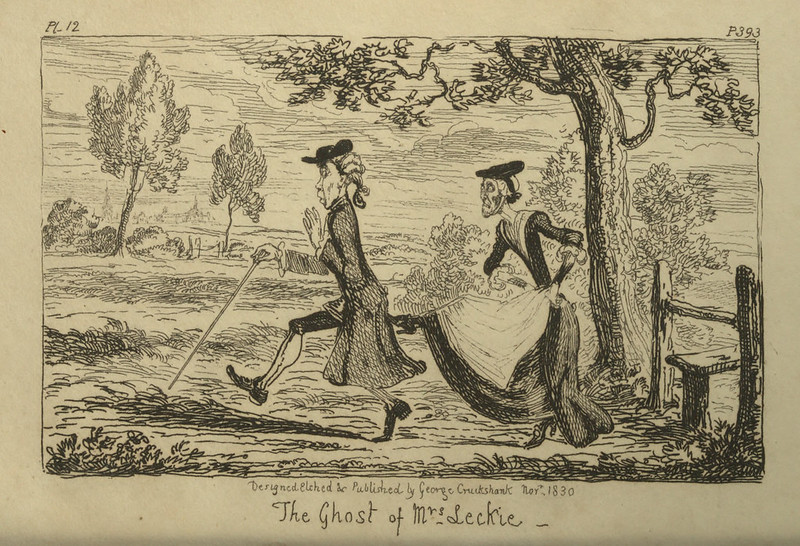

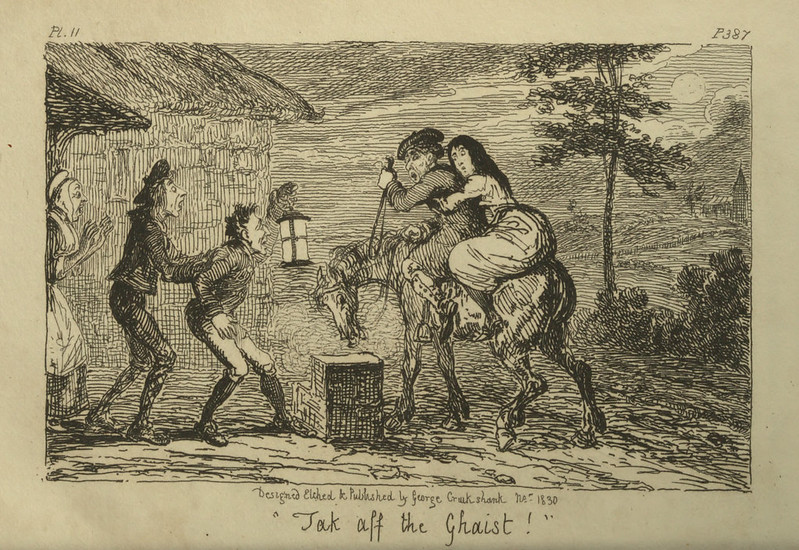

Lockhart's suggestion was partly sparked by the interest raised by Robert Pitcairn's serial publication of Criminal Trials of Scotland, covering proceedings between 1487 and 1624, and featuring many cases of witchcraft. Pitcairn himself sent Scott transcripts of as yet unpublished trials, and many other students of the occult sent Scott source material on witchcraft while he was working on the Letters. In addition, he drew on earlier demonologies such as Reginald Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft, Robert Kirk's Essay on the Subterranean Commonwealth, and Cotton Mather's Magnalia Christi. Scott's arguments against a supernatural explanation of such phenomena were influenced by John Ferriars's 'Of Popular Illusions and More Particularly of Modern Demonology' and Thomas Jackson's Treatise Containing the Originall of Un-beliefe. Composition was rapid, with the volume complete by mid-July 1830, but Scott's interest waned long before the last page. It was published on September 14, 1830, with ten illustrations by George Cruickshank.

The book takes the form of ten letters addressed to Lockhart, the epistolary mode permitting Scott to be both conversational in tone and discursive in method. In these, Scott surveys opinions respecting demonology and witchcraft from the Old Testament period to his own day. As a child of the Enlightenment, he adopts a rigorously rational approach to his subject. Supernatural visions are attributed to 'excited passion', to credulity, or to physical illness. The medieval belief in demons is based on Christian ignorance of other religions, leading to the conviction that the gods of the Muslim or Pagan nations were fiends and their priests conjurers or wizards. In the post-Reformation period, the primitive state of science and predominance of mystical explanations of natural phenomena fed fear of witchcraft. In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, witches were hunted with near-hysterical zeal. Examining Scottish criminal trials for witchcraft, Scott notes that the nature of evidence admissible gave free reign to accusers and left the accused no chance of escape. Prisoners were driven to confess through despair and the desire to avoid future persecution. Scott also observes that trials for witchcraft were increasingly connected with political crimes, just as in Catholic countries accusations of witchcraft and heresy went together. Advances in science and the spread of rational philosophy during the eighteenth century eventually undermined the belief in supernatural phenomena, although pockets of superstition remain. Scott's account is amply illustrated with anecdotes and traditional tales and may be read as an anthology of uncanny stories as much as a philosophical treatise." - quote source

Image sources include archive.org and Bloomsbury Auctions.

No comments:

Post a Comment